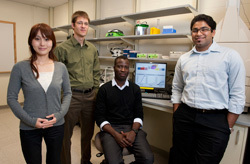

Most winners of the DREAM Challenge, an international competition in systems biology, are teams of Ph.D.-level scholars—computer scientists from major universities as far-flung as Singapore, Switzerland, Italy, and Sweden. This year, the winning team is from Notre Dame. They are the Fighting Irish Systems Team, or FIrST, led by biology graduate student and 2009 Eck fellow Geoffrey Siwo. The team includes biology graduate student Richard Pinapati, computer science graduate student Andrew Rider, and laboratory technician Asako Tan who, with Siwo, are all affiliated with the Interdisciplinary Center for Network Science and Applications (iCeNSA).

The DREAM (Dialogue on Reverse Engineering Assessment Methods) Challenge issued four challenges. The one answered by Siwo's group presented the teams with a gene sequence and asked them to predict how much protein a yeast cell would produce when the sequence was introduced into it.

FIrST's success is unprecedented, not only because of the team's youth, but also because of its specialization in biology rather than mathematics or computer science. Associate Professor of Biological Sciences Michael Ferdig, whose malaria research lab is home to Siwo, Pinapati, and Tan, says that the biologists' win “cuts to an important point: the modern era of bioscience is about massive datasets that can be made by new technologies, and the need for computational innovation is huge – but the computation is only as strong as the biology understanding that is built into the algorithms.” The members of FIrST are examples of “a new breed of biologists, comfortable moving across classical bio and computational innovation. This never happened even a few years ago.”

Though the field is in its early days, a method of consistently extrapolating cell phenotypes from gene sequences carries broad implications for medicine, engineering, and research. Eventually, using sequences designed via computer, human cells could be instructed to deliver a certain amount of a given protein; biofuels could be produced on demand; proteins could be easily synthesized for lab use.

It is collaboration -- both between teammates and between competitors -- that Siwo finds inspiring about his work on the DREAM challenge. “When you bring several humans together,” he says, “focus them on a well-defined challenge, and let them work independently in small teams, something special happens. Collective intelligence: a group intelligence that emerges from collaboration and competition.” Each team's solution is slightly different, and each one, even the best, is incomplete. The true answer is the sum of all answers. “This,” says Siwo, “is what I think is the greatest lesson beneath the surface and what makes DREAM an important step in the search for a convergence between theory and experiment.”