As we mark the one year anniversary of the death of Fr. Hesburgh, the College of Science recalls and appreciates the impact that he had on science at Notre Dame.

When former Notre Dame President Father John J. Cavanaugh challenged “Where are the Catholic Salks, Oppenheimers, and Einsteins?” in a widely-read essay in the late 1950s, Father Theodore Hesburgh was already in the process of providing an answer. In both direct action, from building facilities to recruiting top scholars, and cultural transformation, from welcoming women students to asserting academic freedom, Hesburgh laid the foundations for the College of Science’s accelerating research, discovery, and mission-driven entrepreneurship in the 21st century.

“Father Hesburgh realized that challenge was being put in his care,” said Anthony Trozzolo, a prominent chemist recruited as one of the first endowed chair professors. “He said ‘we’ve got to upgrade the students, the faculty, and the buildings.’ He was very vigorous in his pursuit of progress in all those three categories.”

Top scholars that Hesburgh brought to campus established world-class programs that continue today and elevated the University’s reputation in a virtuous cycle that brings more respected researchers and sought-after students.

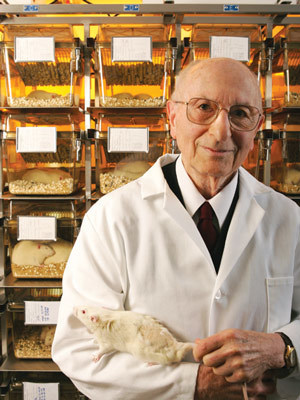

Morris Pollard

When he was a veterinary student at Ohio State University in the 1930s, Morris Pollard successfully isolated the first retrovirus. During World War II, he discovered that a tick bite was responsible for the mysterious death of soldiers at Camp Bullis near San Antonio, the plague ended in a cloud of DDT, and Pollard won the Army Meritorious Service Award. He became the youngest full professor at the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston, where a postdoctoral fellow named Raphael Wilson from the University of Notre Dame came to work in his lab.

When Wilson, a Holy Cross brother, told Father Hesburgh about Pollard, Hesburgh recruited him to revive the Laboratories of Bacteriology at the University of Notre Dame (LOBUND) research facility in 1961 – the first Jewish professor on campus and a harbinger of the expanding diversity of researchers who share the mission of elevating individual and social wellbeing. “You’ll fit in fine,” Hesburgh told him. “All of us at Notre Dame are trying to get out of our own ghettoes.”

“Father Hesburgh had the view, ‘why should a Catholic university of the first order exclude outstanding people from their faculty, unrelated to whatever their religion should happen to be?’” said Pollard’s son, Harvey, a physician who works at the Uniformed Services School of Medicine. For his part, Pollard declined Hesburgh’s offer to remove classroom crucifixes in the Department of Biological Sciences.

Pollard, who attracted more than $250 million in research funding during his career, focused on viruses growing in the germ-free LOBUND. He noticed that a certain rat in the setting developed prostate cancer; when he tested whether the germ-free environment caused the onset by putting the rats in an ordinary setting, they continued to develop the cancer. The Lobund-Wistar rat line remains an important model for studying cancer 45 years later, and Pollard, who died in 2011, continued to conduct prostate cancer research well into his 90s.

“Morris Pollard made many remarkable discoveries and was a pioneer of cancer research at Notre Dame,” said Crislyn D'Souza-Schorey, the Morris Pollard Professor and Biological Sciences Department Chair, who met Pollard when he was in his 80s and often chatted about recent cancer discoveries. “He epitomized Fr. Ted’s legacies of avoiding ‘the taint of intellectual and moral mediocrity’ and being willing ‘to be a minority of one if need be.’ He loved Notre Dame and referred to it as home.”

Anthony Trozzolo

A full weekend of festivities marked the inauguration of Anthony Trozzolo as the Charles L. Huisking Professor of Chemistry in November 1975, a giant step for Father Hesburgh’s plan to create endowed chairs that would attract top research faculty to Notre Dame. Hesburgh introduced the Huisking family at a formal dinner on Friday after he celebrated a Memorial Mass for Charles and Catherine Huisking. The Trozzolo family had 50-yard-line seats at the football game the next day, a historic contest later depicted in the movie Rudy.

Trozzolo, who left a flourishing 16-year career at Bell Laboratories in New Jersey to join Notre Dame, first visited the campus in 1972 when he gave the prestigious Reilly Lectures. Hesburgh explained the endowed chair strategy at lunch in an upstairs nook at the Morris Inn at the end of a round of interviews in 1974.

“He painted a vision of what he hoped to accomplish in the next few years,” Trozzolo said. “One of the aims he had was to try to endow every full professor. We certainly have a lot more endowed chairs at the University than we had in 1974. He recruited me as the first endowed chair professor in chemistry.”

The program enables the University to recruit top faculty to vacancies rather than hiring entry-level professors who would take years to build their research programs and reputations. Trozzolo, among other things, had founded the Gordon Conference on Photochemistry in 1964.

Trozzolo, who was concurrently appointed to the Radiation Lab, was inspired by Hesburgh’s commitment to make Notre Dame a top-tier Catholic research institution, and the president promised that a new building for the department, Stepan Chemistry, was at the top of his facilities list. Hesburgh’s opening the University to women was an important factor–Trozzolo’s two sons and four daughters all attended Notre Dame and earned six degrees among them.

High-Energy Physics Group

Paul Kenney and William Shephard were looking to find a place to expand their elementary particle physics research in 1963 when Father Hesburgh offered them faculty positions and a chance to start a High Energy Physics Group at Notre Dame. The group, with international collaborations and experiments at Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, Argonne National Laboratory, and CERN, is now a world-renowned contributor in the field.

“The group has played key roles in the discoveries of two of nature’s most important particles, the top quark and the Higgs boson, as well as the theoretical and experimental study of the difference between matter and anti-matter, which is vital for understanding why our universe contains any matter at all,” says Christopher Kolda, Chair of the Department of Physics.

“Father Hesburgh was knowledgeable in physics and knew elementary particle physics was a field of the future,” Shephard recalls. “He wanted to start a group here. He continued to support the group throughout his presidency.”

John Poirier joined the group after one year, followed by Neal Cason and John LoSecco. Early research involved scanning, measuring, and reconstructing events found on cloud chamber and bubble chamber pictures. The group now has six experimental and four theoretical teaching and research faculty, research faculty, postdoctoral associates, and graduate students, and attracts funding from the U.S. Department of Energy as well as the National Science Foundation.

Poirier, who later went on to focus on another specialty, recalls when the College of Science was in The Huddle and Nieuwland Science Hall was under construction, he helped move the important Van de Graaff particle accelerator to Nieuwland from the basement when he was an undergraduate. Years later, he happened to sit next to Father Hesburgh on a flight to South Bend after conducting research at a major laboratory and was astonished at the University president’s familiarity with the work.

“I was just amazed at how much he knew about what was going on,” Poirier said. “He could carry on a good conversation and be interested in what we were doing, where we were coming from, and what we were up to. He knew a lot more detail about what we were doing than I could ever imagine the president would.”