James Hentig joined the U.S. Army at 17, never even expecting to attend college, but a traumatic brain injury (TBI) the fourth-year doctoral student sustained in 2010 as an Airborne Medic in Afghanistan now informs his quest to help others suffering from similar conditions.

“Honestly, I joined the Army because I was scared to go to college,” Hentig said. “Life changed very quickly - I had no intention of going to school. But through the GI Bill they pay not just for your schooling but as well as a stipend for you to live on.” At first, he saw higher education as “an easy way to make a living for a little bit.”

But in his first year at the Western Michigan University, Hentig discovered his passion for science, and his interest never waned. Now, he is receiving national recognition for his research on the brain.

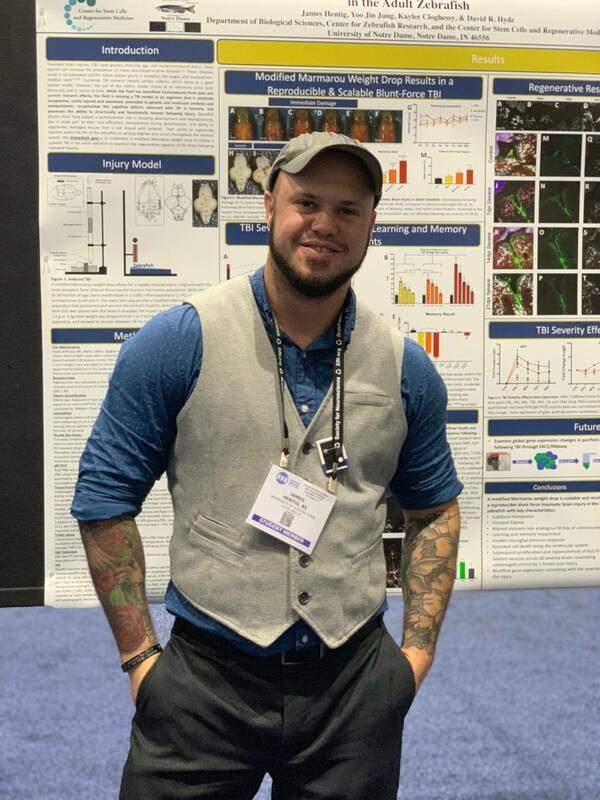

Hentig recently presented his work on the long-term progression of TBIs on zebrafish and their subsequent cell regeneration at the Society for Neuroscience’s (SfN) annual conference, a meeting of 35,000 professionals in various fields to present and discuss neuroscience research.

The society chose Hentig as one of 15 students to participate in the inaugural class of the society’s Leadership Development Program (LDP), which will provide “high-quality leadership training talented early-career neuroscientists,” according to SfN President Diane Lipscombe.

Hentighad already received special recognition as a recipient of the society’s Trainee Professional Development Award (TPDA), given to 200 of 1800 undergraduates, graduate students, and postdoctoral fellows who “demonstrate scientific merit and excellence in research,” as stated on SfN’s website. TPDA winners benefit from this distinction by receiving travel grants and access to special development courses.

However, Hentig did not always want to be a scientist. Early in his time at Western Michigan, Christine Byrd-Jacobs, one of his professors, noticed that he had a lot more background knowledge on neurological conditions than his classmates, because he had conducted extensive internet research on traumatic brain injuries when he did not receive sufficient information on his own. Recognizing his unique experience, Byrd-Jacobs invited Hentig to work in her neuroscience lab.

Although Hentig enjoyed his research, with his prior service as an army medic, he hoped to someday go to medical school and save more lives. However, a conversation with Byrd-Jacobs changed the course of his own life yet again.

“She asked me, ‘Well, why? Why do you want to be a doctor? How do you want to help people?’” Hentig remembers. “And I told her, ‘Well, I don’t like the fact that we run out of options...That’s what happened to me with my traumatic brain injury. We tried a bunch of things and they eventually said, “We’re sorry, that’s the end of the list.”’ And I told my advisor, ‘I’m really interested in adding to that list.’”

“She explained to me that’s what research is, that’s what graduate school is, that’s what becoming a scientist is.”

While physicians have only a limited number of resources to work with when treating patients with traumatic brain injuries, Hentig hopes to expand the list of therapeutic options with his research. His work will not just benefit members of the military, like himself, but everyone.

“Anyone and everyone is susceptible [to traumatic brain injury],” Hentig explains. “It doesn’t matter your age, your race, your ethnicity, your social class.”

While 60 million people report traumatic brain injuries per year, or about 3,000 people every half hour, Hentig estimates that if one takes unreported incidents into account, the number quadruples. In addition to immediate physical pain and mental damage, TBIs can increase one’s risk of Alzheimers, Parkinsons, ALS, and Frontal-Temporal Dementia. Hentig wants to alleviate this suffering.

“They have all the same genes that we do, but they can turn them on in different patterns than we can,” Hentig describes.The graduate student has begun his research by modeling the effect of these injuries on the brain, with the goal of not just mitigating the symptoms of TBIs but healing the disease completely. He works with zebrafish, an organism with a unique ability to grow new brain cells.

Because of this unique gene expression, within a few days of sustaining a TBI, zebrafish stem cells start moving into the cerebellum and replacing the dying ones. If humans could harness the same neuroregenerative potential as zebrafish, then Hentig hopes this ability could provide a therapeutic cure for traumatic brain injury.

Hentig said he was excited and shocked to be one of 15 of the inaugural cohort in SfN’s leadership program. He will receive funding, leadership training, and an invitation to a conference in Washington, D.C. in early 2020. He particularly looks forward to the mentorship opportunities that this program will provide, as he is “interested in meeting a wider range of individuals who have been successful in their careers.” While Hentig appreciates all of the support he has received at Notre Dame, he wants to learn about the leadership skills of diverse people in the industry across the country.

Someday, Hentig hopes to gain his own mentorship position in the pharmaceutical industry. His participation in the LDP will help him develop skills such as motivating his coworkers, conducting hard conversations, and creating a happy, safe work environment, so that he can serve as a role model to his employees. In the future, Hentig would like to improve lives not just by treating diseases but also serving as a mentor, in the same way Byrd-Jacobs helped him as an undergraduate and the LDP will enhance his graduate experience.

But for now, Hentig is focusing on his zebrafish research and earning his doctoral degree.

“Graduate school is where you start to examine and push those boundaries and add to that list, be able to add new therapeutic options. And so, that’s what really started to drive me to science. I was interested in helping people...I want to give them something new that they can try when they’ve tried everything else,” he said.