Victor Riemenschneider

Victor Riemenschneider

South Bend biologist Victor Riemenschneider spent his professional life collecting, preserving and mounting plants from northern Indiana. An associate professor emeritus of biology at Indiana University-South Bend (IUSB), he was in a quandary about where to keep his collection for posterity.

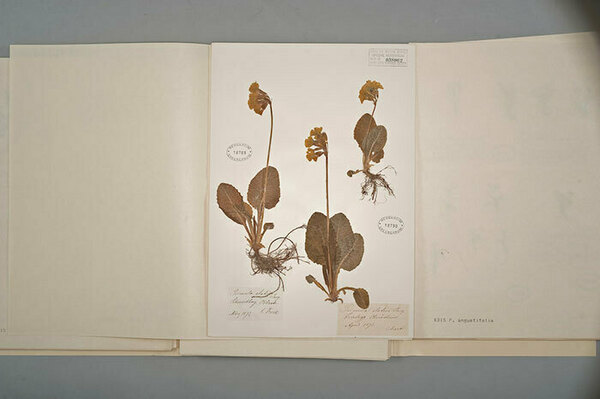

Because IUSB did not have a herbarium, essentially an environmentally controlled library of mounted plant samples, he knew he could not safely keep his 759-piece collection there. The IU-Bloomington campus contained a herbarium, but the curator was retiring when Riemenschneider started considering donating his collection, bringing the fate of his life’s work into question. Also, if the collection was moved out of the area, Riemenschneider feared knowledge of plant distribution since the 1970s, essential in pinpointing signs of climate change or other issues, could be lost.

Barbara Hellenthal

Barbara Hellenthal

Notre Dame’s Greene-Nieuwland Herbarium, however, was stable. It was also the largest herbarium in the state and a recognized repository for specimens and information resulting from state research of the flora. And Riemenschneider knew Barbara Hellenthal, the curator who cares for the herbarium’s 280,000 preserved plants collected from the early 1800s to the present. Each plant specimen (including berries and pine cones) is carefully filed in folders and stored in floor-to-ceiling cabinets in the museum, located on the first floor of Jordan Hall. So Riemenschneider entrusted his collection to Notre Dame.

Riemenschneider and Hellenthal both stressed the importance of specimen collection for understanding plant evolutionary relationships. Failing to collect a species can create holes in knowledge. For example, Riemenschneider discovered plants in the late 1970s or early 1980s in Pulaski County’s Sandhill Nature Preserve that were actually coastal plant species pushed there from the Ice Age, growing in the sand where trees were only beginning to sprout.

“I didn’t collect that one—in those days, when I first started collecting nature preserve plants, it was more restrictive,” he said, adding that not preserving this plant is one of his deepest professional regrets. “Now it’s all forested and I don’t even know if the plant is there anymore. This is not an argument for someone to do wanton collecting, but it’s important for scientists to collect species for study over time.”

Not finding a plant where it was collected years ago is just as crucial as discovering a new plant. “It improves our knowledge of how distribution is changing, and these different discoveries are useful,” Hellenthal added.

Riemenschneider is pleased that his work will be preserved, and Hellenthal’s students are continuing to label and catalog the folders that contain the different plants. Riemenschneider’s plants are currently in a separate cabinet, but once they’re logged, they’ll be merged with the rest of the university’s collection.

“We appreciate that he donated his collection to us. This is his life’s work; a valuable collection and good representation of the plants in this part of the Chicago region,” Hellenthal says. “His collection will continue to support research of the state’s flora. The value of any collection increases over time, because researchers never know what types of situations will arise that will require study and comparison with the flora collected decades ago.”