Yanting “Raven” Luo knew she would have to speak a different language when coming to college in the United States, but she did not realize she would discover whole new ways to talk about the world around her through science.

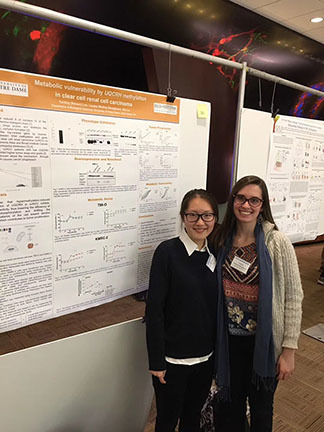

The Notre Dame senior, who is majoring in Biological Sciences on the Computational Biology track, received the opportunity to present her research on the UQCRH gene and kidney cancer at the Midwest Metabolism Meeting last fall.

However, Luo did not always see science as her academic path. Growing up in Shanghai, China, she always thought she would study English when she attended university and even went to a foreign-language middle school.

“But then in high school they started teaching biology from the level of molecules, and then I learned about how, basically, there is this language of life, where you have molecules interacting and producing signaling pathways,” Luo said. She decided to study biology, because this branch of science explores the way in which “basically everything that [she] knows and loves” communicates.

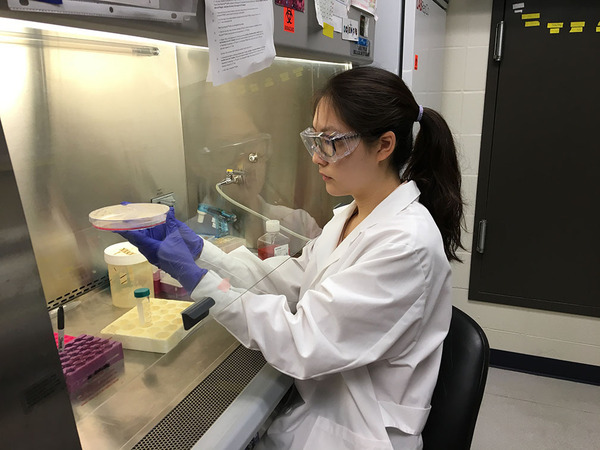

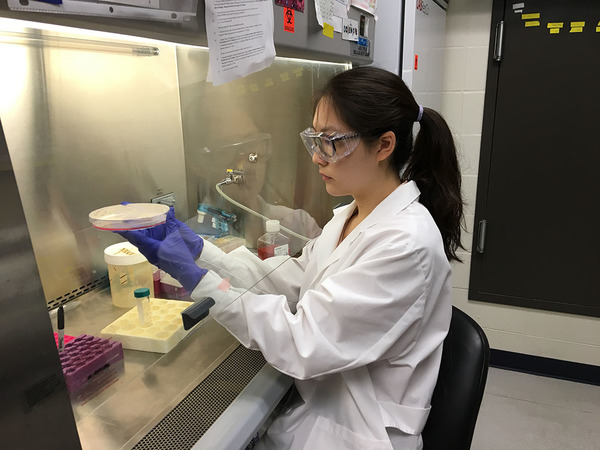

Luo has maintained her fascination with languages in a more traditional manner by pursuing a supplementary major in Japanese. But she also uses the new language of science in her research at Notre Dame. In the lab of Dr. Xin Lu, the John M. and Mary Jo Boler Assistant Professor in the Department of Biological Sciences, Luo investigates how low levels of the mitochondrial gene UQCRH affect the energy and metabolism of kidney cancer cells, with the hope of treating clear-cell renal carcinoma (CCRCC).

Luo joined Lu’s lab upon a recommendation from her introductory biology professor, who knew that the now-senior had developed an interest in cancer research during an internship project in high school. The impetus to study the UQCRH gene came from a five-lab collaboration on Von Hippel-Lindau disease (VHL), a rare inherited condition which causes patients to develop tumors in their organs. CCRCC tumors often occur in people with VHL, although many kidney cancer patients who do not have this heritable disease also suffer from clear-cell renal carcinoma.

While looking into Von Hippel-Lindau disease, Luo found a computational biology paper which noted that low UQCRH gene expression was one of the most common traits in CCRCC patients. Researchers have also observed that people with lower levels of the protein UQCRH produces experience worse tumor progression. Yet not much is known about this potentially pivotal gene and the protein whose coding information it contains.

“There are only 25 papers that I could find that even mention this protein,” Luo said. “And I think we know very little about it, but it could potentially be important in [CCRCC], or even if not, I think the understanding that we get from it is valuable in terms of looking at the big picture of cancer.”

After researching UQCRH behavior, Luo’s group hypothesizes that the metabolism in cancer cells without enough of the protein “goes haywire,” so that they generate energy abnormally. Usually, it is most efficient for cells to metabolize using oxygen, but clear-cell carcinomas pursue other methods of making energy. Luo believes that these cancers might behave in this manner to sustain uninhibited cell growth, a deadly characteristic of the disease.

In fact, one of the reasons cancer is so often fatal is that each form of the disease behaves differently. So, doctors must tailor the most effective treatments to the specific attributes of a certain type of cancer. If her connection between the UQCRH and kidney cancer cell metabolism proves meaningful, Luo and her team propose that they could use a high-fat, low carbohydrate ketogenic diet to potentially treat clear-cell renal carcinoma. This diet may starve cancer cells of energy, when they refuse to metabolize with oxygen and cannot break down fat, but it will not harm normal, healthy cells.

Along with another Notre Dame student, sophomore neuroscience and behavior major Louise Medina Bengtsson, Luo presented these ideas at the Midwest Metabolism Meeting in Grand Rapids, Michigan, last fall. 2019 was only the second year that this conference took place, after debuting at Notre Dame in 2018 when Dr. Zachary Schafer, Coleman Foundation Associate Professor of Cancer Biology, and colleagues at other institutions noticed an emerging focus on metabolism research in the midwest.

“Last year, I was just an audience member, and the project was in its beginning stages,” Luo remembered. When she attended the first Midwest Metabolism Meeting, Luo was inspired to study the connections between cancer and cell energy use, but this year, she could share her discoveries with others. At the conference, Luo received suggestions that she had never considered before, and she made connections with researchers in the field that could help support her work in the future.

Luo also sees the sense of collaboration and conversation she experienced during the Midwest Metabolism Meeting at Notre Dame as a whole. Although she is willing to explore various possibilities in the near future, just as she decided to attend college in a new country and study a new subject, she knows that she wants to keep pursuing the life sciences. She will continue to use the language of biology to foster further discussion scientific discussion, with the hope of improving lives.

“I think my ultimate goal, and that’s pretty set, is to be a scientist [who] could serve my community,” Luo said. “I think that’s something that the Notre Dame education taught me. I want to be a scientist, but I also want to use the knowledge I have to solve problems that exist today.”